Biography

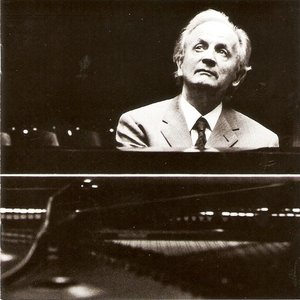

Herbert von Karajan (Salzburg April 5, 1908 Anif near Salzburg – July 16, 1989) was an Austrian conductor. His New York Times obituary called him “probably the world’s best-known conductor and one of the most powerful figures in classical music,” and placed him “in the topmost ranks of 20th-century conductors.” Karajan conducted the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra for thirty-five years.

Herbert von Karajan was the son of an upper-bourgeois Salzburg family of Greek ancestry. His great-great-grandfather, Georgeous Johannes Karajanis (Greek: Γεώργιος Ιωάννης Καραγιάννης), was born in Kozani, at that time a town in the Ottoman Empire (now in Greek Macedonia), and left for Vienna in 1767, eventually moving to Chemnitz in Saxony. He and his brother participated in the establishment of Saxony’s cloth industry, and both were ennobled for their services by Frederick Augustus III on June 1, 1792 (thus adding the “von” to the family name). The Karajanis name became Karajan.

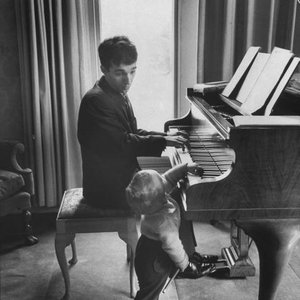

Herbert von Karajan was born in Salzburg as Heribert Ritter von Karajan (ref R Osborne’s biography mentioned below). From 1916 to 1926, he studied at the Mozarteum in Salzburg, where he was encouraged to study conducting.

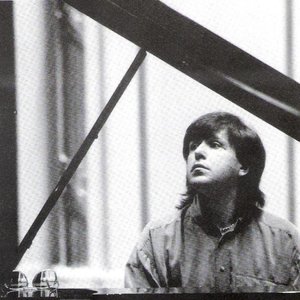

In 1929, he conducted Salome at the Festspielhaus in Salzburg, and from 1929 to 1934, Karajan served as first Kapellmeister at the Stadttheater in Ulm. In 1933, Karajan made his conducting debut at the Salzburg Festival with the “Walpurgisnacht Scene” in Max Reinhardt’s production of Faust. The following year, and again in Salzburg, Karajan led the Vienna Philharmonic for the first time, and from 1934 to 1941, Karajan conducted opera and symphony concerts at the Aachen opera house.

In March of 1935, Karajan’s career was given a significant boost when he applied for membership in the Nazi Party. (‘Aufnahmegruppe der 1933er, nachgereichte’) That same year, Karajan was appointed Germany’s youngest “Generalmusikdirektor” and was a guest conductor in Brussels, Stockholm, Amsterdam, and other European cities. Moreover, in 1937, Karajan made his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic and the Berlin State Opera with Fidelio. He enjoyed a major success with Tristan und Isolde and in 1938, was hailed by a Berlin critic as “Das Wunder Karajan” (“The Karajan miracle”). Receiving a contract with Deutsche Grammophon that same year, Karajan made the first of numerous recordings by conducting the Staatskapelle Berlin in the overture to Die Zauberflöte. However Adolf Hitler had only scorn for the famed conductor after he fumbled at one point in a gala performance of “Die Meistersinger” for the King and Queen of Yugoslavia in June 1939. Conducting without a score, Karajan lost his way, the singers halted, the curtain was rung down in confusion. Furious, Hitler directed Winifred Wagner : “Herr von Karajan will never conduct at Bayreuth in my lifetime”, and he did not. After the war, Karajan did his best to prevent the evocation of this shameful and not too glorious incident that perhaps saved his post-war career.

On October 22, 1942 at the height of the war, Karajan married Anita Gütermann, the daughter of a well-known sewing machine magnate, and who, having a Jewish grandfather, was considered to be Vierteljüden (one-quarter Jewish). Within days of the wedding, “things started turning nasty” when the NSDAP opened an enquiry into whether or not Karajan was exempt from the Party’s racial laws. Karajan apparently verbally tendered his resignation from the Party, but was kept on as a Party member, either because the resignation was not submitted in writing, or Party leaders felt he was better used conducting concerts. However, Karajan’s conducting career now took a definite turn for the worse, and by 1944, he was on the outs with the Nazi leaders. Karajan conducted his final concert in wartime Berlin on Feb 18, 1945 and, fearing for his life, fled Germany with Anita for Milan a short time later (Source: R. Osborne, “Karajan: A Life in Music”). Karajan and Anita divorced in 1958.

Karajan was deposed by the Austrian denazification examing board on March 18, 1946 and resumed his conducting career shortly thereafter (Karajan’s deposition is presented in whole as Appendix C of Richard Osborne’s biography cited above).

In 1946, Karajan gave his first post-war concert, in Vienna with the Vienna Philharmonic, but he was banned from further conducting activities by the Russian occupation authorities because of his Nazi party membership. That summer, he participated anonymously in the Salzburg Festival. The following year, he was allowed to resume conducting.

In 1948, Karajan became artistic director of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, Vienna. He also conducted at La Scala in Milan. However, his most prominent activity at this time was making recordings with the newly-formed Philharmonia Orchestra in London. He built the orchestra into one of the world’s finest.

In 1951 and 1952, he conducted at the Bayreuth Festspielhaus.

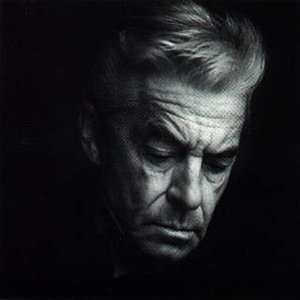

In 1955, he was appointed music director for life of the Berlin Philharmonic as successor to Wilhelm Furtwängler. From 1957 to 1964, he was artistic director of the Vienna State Opera. He was closely involved with the Vienna Philharmonic and the Salzburg Festival, where he initiated the Easter Festival, which would remain tied to the Berlin Philharmonic’s Music Director after his tenure. He continued to perform, conduct, and record prolifically until his death in 1989.

Karajan played an important role in the development of the original compact disc digital audio format (circa 1980). He championed this new consumer playback technology, lent his prestige to it, and appeared at the first press conference announcing the format. Early CD prototypes had exhibited a playing time limited to a mere sixty minutes. It is often asserted that the decision to extend the maximum playing time of the compact disc to its standard of seventy-four minutes was achieved in order to adequately encompass Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the existing library of Karajan’s recordings, and his expressed wishes. However, it is also possible that this story is an urban legend.

As was the case with soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Karajan’s membership in the Nazi Party and prominent cultural association with Nazism from 1933 to 1945 cast him in an uncomplimentary light after the war. While Karajan’s defenders have argued that he joined the Nazis only to advance his own career, his critics have pointed out that other great conductors such as Bruno Walter, Erich Kleiber and Arturo Toscanini fled from fascist Europe at the time (although it should be noted that many famous conductors worked in Germany throughout the war years, including Furtwängler, Ansermet, Schuricht, Böhm, Knappertsbusch, Clemens Krauss, Rother and Elmendorff). Additionally, careerism could not have been Karajan’s sole motivation, since he first joined the Nazi Party in 1933 in Salzburg, Austria, five years before the Anschluss. In The Cultural Cold War (published in Britain as Who Paid the Piper?), her book on CIA cultural policy in postwar Europe, Frances Stonor Saunders noted that Karajan “had been a party member since 1933, and never hesitated to open his concerts with the Nazi favourite ‘Horst Wessel Lied.’”(Note: Karajan attempted to join the Party in 1933, but his application was rejected and he did not follow up on the application. His initial application was assigned a provisional membership number that was later declared to be invalid. Karajan formally joined the Party only once - in 1935. Source: Osborne) Additionally and in contradistinction to Furtwängler, Karajan had no objections to conducting in occupied Europe (though Furtwängler continued to conduct in Germany throughout the war. Furtwängler was, after all, the music director of the Berlin Philharmonic, before and throughout the war until his death in 1954). Musicians such as Isaac Stern and Itzhak Perlman refused to play in concerts with Karajan because of his Nazi past. Some have questioned whether Karajan was committed to the Nazi cause given the fact of his marriage in 1942 to Anita Guetermann, a woman of clear Jewish origin. Karajan’s star within the government dimmed from that point.

There is widespread agreement that Herbert von Karajan had a special gift for extracting beautiful sounds from an orchestra. Opinion varies concerning the greater aesthetic ends to which The Karajan Sound was applied. The American critic Harvey Sachs, a fervent Toscanini admirer, among other things, and far from an impartial observer, criticized the Karajan approach as follows:

Karajan seemed to have opted instead for an all-purpose, highly refined, lacquered, calculatedly voluptuous sound that could be applied, with the stylistic modifications he deemed appropriate, to Bach and Puccini, Mozart and Mahler, Beethoven and Wagner, Schumann and Stravinsky… many of his performances had a prefabricated, artificial quality that those of Toscanini, Furtwängler, and others never had… most of Karajan’s records are exaggeratedly polished, a sort of sonic counterpart to the films and photographs of Leni Riefenstahl.

However, it has been argued by commentator Jim Svejda and others that Karajan’s pre-1970 manner did not seem as calculatedly polished as it is later alledged to have become.

This characteristic style struck many listeners as yielding different degrees of success in music of different eras. Web data suggest that, of Karajan’s numerous recordings, those of mainstream nineteenth century Romantic repertory often attract the greatest admiration (many regard his 1962 recording of the Beethoven symphonies as the yardstick for all other performances of these pieces.) He was simply peerless in the music of Anton Bruckner or Robert Schumann. But von Karajan’s work in music of the Baroque or Classical periods is not at present fashionable outside Germany and Austria.

Two reviews, arguably representative of British and American opinion, from the widely-read Penguin Guide to Compact Discs can be quoted to illustrate the point.

* Concerning a recording of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, a canonical Romantic work, the Penguin authors wrote “Karajan’s is a sensual performance of Wagner’s masterpiece, caressingly beautiful and with superbly refined playing from the Berlin Philharmonic … an excellent first choice.”

* About Karajan’s recording of Haydn’s “Paris” symphonies, the same authors wrote, “big-band Haydn with a vengeance … It goes without saying that the quality of the orchestral playing is superb. However, these are heavy-handed accounts, closer to Imperial Berlin than to Paris … the Minuets are very slow indeed … These performances are too charmless and wanting in grace to be whole-heartedly recommended.”

(The same Penguin Guide does nevertheless give the highest compliments to von Karajan’s recordings of the selfsame Haydn’s two oratorios, The Creation and The Seasons.)

As for twentieth century music, Karajan was criticized for having conducted and recorded pre-1945 works almost exclusively (Mahler, Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, Bartók, Sibelius, Richard Strauss, Puccini, Ildebrando Pizzetti, Arthur Honegger, Prokofiev, Debussy, Ravel, Paul Hindemith, Carl Nielsen and Stravinsky), although he did record Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10 (1953) twice, and did premiere Carl Orff’s “De Temporum Fine Comoedia” in 1973.

Some critics, particularly British critic Norman Lebrecht, charged Karajan with initiating a devastating inflationary spiral in performance fees. During his tenure as director of publicly-funded performing organizations such as the Vienna Philharmonic, the Berlin Philharmonic, and the Salzburg Festival, he started paying guest stars exorbitantly, as well as ratcheting up his own remuneration:

Once he possessed orchestras he could have them produce discs, taking the vulture’s share of royalties for himself and rerecording favorite pieces for every new technology until he died (digital LPs, CD, videotape, laserdisc). In addition to making it difficult for other conductors to record with his orchestras, von Karajan also drove up the prices that he would be paid and thus other conductors wanted.

During a rehearsal of the Beethoven Triple Concerto with David Oistrakh, Sviatoslav Richter and Mstislav Rostropovich, pianist Richter asked Karajan if they could go over a passage again, to which Karajan replied “No, now it is time for pictures”. This did not prevent violinist Oistrakh from saying, when Karajan turned 65, that he was “the greatest living conductor, a master in every style.”

Finally, Karajan was held by some to be excessively egotistical. When he conducted Wagner at the Metropolitan Opera, he raised the conductor’s stand to place himself in the line of sight of the audience; in operatic recordings of Verdi, he changed the balance so as to bring the sound of the orchestra forward in the final mix, all to emphasize his role in the music-making. Critics compare him with Leonard Bernstein, pointing out both conductors were “unequaled in their mastery of podium histrionics.” In fact, with his intimately known Berlin group Karajan frequently recalled Fritz Reiner in his economy of motion. He also often conducted with his eyes closed. Many were the legendary “anecdotes” purporting to illustrate his (undeniably colossal) ego. According to one, Karajan gets into a waiting limousine in Vienna and the driver asks him where he wishes to go. “It does not matter”, he responds, “I’m wanted everywhere.” He did have a wicked and highly irreverent sense of humour.

Karajan’s DG recording of Johann Strauss’ An der schönen, blauen Donau (The Blue Danube waltz) was used by director Stanley Kubrick for a sequence in the science-fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey (with Kubrick animating the sequence to match the prerecorded music—the opposite of the usual practice for soundtracks). The popular effect of this unconventional use of the music was such that the music arguably became more identified with space stations (as depicted in the film) for subsequent generations than with the dances for which the composer intended it. Kubrick also used Karajan’s Decca recording of Richard Strauss’s tone poem Also Sprach Zarathustra for the opening sequence of the film, thereby giving Strauss’s piece a wider fame than it had hitherto had. Some years later, Kubrick again used Karajan’s recordings, this time Béla Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta in The Shining. Although there is a 1958 version by Ferenc Fricsay of the second movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film A Clockwork Orange, the symphony’s finale we hear at the end of the movie is actually Karajan’s now-famous 1963 recording. These two versions featured in the film are both from DG and both performed by the same orchestra, The Berlin Philharmonic.

*** Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra ***

The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra was founded in Berlin in spring 1882 by 54 musicians under the name Frühere Bilsesche Kapelle (former Bilse’s Band); the group broke away after their previous conductor Benjamin Bilse announced his intention of taking the band on a fourth class train to Warsaw for a concert. The orchestra was given its current name and reorganized under the financial management of Hermann Wolff in 1887. Its first conductor under the new organization was Ludwig von Brenner; in 1887 Hans von Bülow, one of the most esteemed conductors in the world, joined, and from then on, the orchestra’s reputation became established, with guests Hans Richter, Felix von Weingartner, Richard Strauss, Gustav Mahler, Johannes Brahms and Edvard Grieg conducting the orchestra over the next few years.

In 1895, Arthur Nikisch became chief conductor, and was succeeded in 1923 by Wilhelm Furtwängler. The orchestra continued to perform throughout World War II, despite several changes in leadership. After Furtwängler fled to Switzerland in 1945, Leo Borchard became conductor. This arrangement lasted only a few months, however; he was accidentally shot and killed by American forces occupying Berlin, and Sergiu Celibidache took over. Furtwängler returned in 1952 and conducted the orchestra until his death in 1954.

His successor was the legendary Herbert von Karajan, who remained with the orchestra until 1989, resigning only months before his death. Under him the orchestra made a vast number of recordings and toured widely. Claudio Abbado became principal conductor after him, expanding the orchestra’s repertoire beyond the core classical and romantic works into more modern 20th century works.

Simon Rattle made it a condition of his signing with the Berlin Philharmonic that it be turned into a self-governing public foundation, with the power to make its own artistic and financial decisions. This required a change to state law, which was approved in 2001, allowing him to join the organization in 2002. The current Intendantin of the orchestra is the American Pamela Rosenberg.

The first concert hall of the orchestra was destroyed during WWII in 1944. The new Berliner Philharmonie was built in 1963 by architect Hans Scharoun at the Kulturforum.

Artist descriptions on Last.fm are editable by everyone. Feel free to contribute!

All user-contributed text on this page is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply.