Biography

-

Born

1904

-

Born In

Tennessee, United States

-

Died

1950 (aged 46)

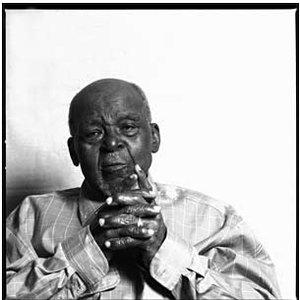

Before World War II St. Louis was a thriving blues town. Henry Townsend, who was an integral part of the St. Louis blues scene during its formative years, had this to say: “It was a whole lotta fun. You didn’t find a dead place in town. Sometimes we’d just get together as a group and just do jamming, you know. Sometimes the jam sessions would last four or five hours. Henry Brown would show up, Peetie Wheatstraw, Robert Johnson was there for a while, and of course Robert Nighthawk, Big Joe Williams, and my main man, Sonny Boy. St. Louis was a hot town for blues in those days, just like Chicago.” Likely encouraged by the discovery of Lonnie Johnson in 1925 the record companies began to focus on St. Louis artists and by 1930 most of the artists of consequence had made their recording debuts. Artists such as Lonnie Johnson, Peetie Wheatstraw, Roosevelt Sykes and Walter Davis went on to enjoy prolific recording careers while the majority are little remembered today, just names on dusty records. St. Louis also boasted some superb woman singers like Bessie Mae Smith, Mary Johnson, Edith North Johnson and one of the city’s best, Alice Moore.

Little Alice, as she was known, achieved a measure of success with her first record, “Black And Evil Blues” cut at her first session 1929 with three subsequent versions cut during the 1930′s. In all she cut thirty-six sides: Two sessions for Paramount in 1929 and nine sessions (the final one went unissued) for Decca between 1934 and 1937. The recording gap was likely due to the depression. Moore possessed a penetrating, pinched nasal tone and tendency to elongate certain words that added to the somber intensity of her songs which were almost always taken at a funeral pace. Mike Stewart and Don Kent described her style this way: “Her singing style, with its particular stresses, and choppy, exclaimed phrasing, was not especially unusual. No one, however, converted it to quite such a mannerism.” She had the good fortune to record with the city’s best musicians including pianists Henry Brown, Peetie Wheatstraw, Jimmie Gordon, possibly Roosevelt Sykes as well as guitarists Lonnie Johnson, Kokomo Arnold and trombonist Ike Rodgers. On record Moore sang mostly hard bitten tales of no good, dangerous men and desperate love in bleak songs like “Lonesome Women Blues”, “S.O.S. Blues (Distress Blues)” “Midnight Creepers” and “Too Many Men.” Prison and prostitution are recurring themes in songs such as “Prison Blues”, “Cold Iron Walls”, “Serving Time Blues” and “Broadway St. Woman Blues.” On record Moore creates a persona of a vulnerable, good woman at the mercy of a cruel world and predatory, indifferent men while at other times she displays the harder shell of a jaded, good-time woman. She sang with conviction, often addressing woman listeners with pointed advice, frequently punctuating her songs with spoken asides and speaking directly to her accompanists.

Little is known of Moore’s background and what is known comes from her arrest files and the recollections of her contemporaries. In fact a photograph of her was published for the first time just recently having been discovered in a 1934 Decca catalog with the caption “Alice Moore, Little Alice From St. Louis.” According to Bill Greensmith: “In March 1925 Alice was arrested twice. The first occasion was on 7 March for ‘suspicion of gambling.’ She gave her address as 2016 Walnut Street, her age as twenty-one, and her birthplace as Tennessee. …She was arrested again on 27 March, although instead of being charged she was sent to the ‘Health Department.’ Alice was living at 2118 Randolph Street when on 19 September 1926 she was arrested and charged with ‘disturbing the peace.’” Henry Townsend told Paul Oliver in 1960: “She was a real nice girl. She was real devoted to her blues singing. From my point of it she was pretty well a nice mixer with the public and a fairly intelligent girl. They used to call her Little Alice – well she was quite small I think at the time they adopted the name to her as Little Alice, but later I think she defeated that name, by getting quite some size – she got extra size before she died about ten or twelve years ago. Henry Brown has played for Alice Moore, for a fact I think he started her out, and she was a devoted blues singer.” In 1986 Townsend told Bill Greensmith: “I remember Alice Moore. She was a beautiful person, a kind-hearted person. She was a very nice looking black gal. She was almost what you would call a pretty girl. She had a beautiful smooth skin like velvet. I think that had a lot to do with her death too. It sounds kinda off the wall, but sometimes a lot of things are against a person that don’t have an understanding about how to handle it. I think it contributed to her living a little fast. Alice Moore, Ike Rodgers, and Henry Brown was a trio. I never worked with them, but I was around them quite a bit. …Alice seemed to be slightly my senior, but not by no big difference. But from maturity, she seemed to be a little more mature than I was. Her ‘Black And Evil’ was a hit right away, that first one. She was a pretty black woman ain’t no doubt about that but the evil part, she wasn’t evil, I don’t think. But I never was her man, and that’s the only way you’re ever going to find that out. She may have been, but she never did show it on the surface; she always showed kindness, everybody like her. I don’t know how Alice died or why. It appears to me like I would have heard about it or somebody would have said something about it, as many people that knew her and me. I’m inclined to believe that Broadway St. Woman Blues 78 whenever she died, it was one of the times that I was away for some reason. A lot of the stuff Alice recorded Henry Brown worked with her, but Jimmy Gordon played piano on one of her sessions.” In 1960 Henry Brown recalled those days: “Henry Townsend played guitar and Little Alice sang. We’d play joints on Franklin … Delmar …Easton … spots in East St. Louis – like the Blue Flame Club.”

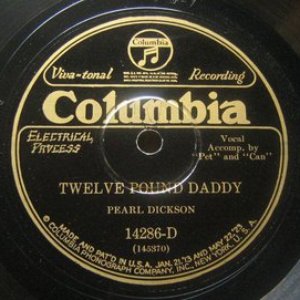

Moore’s first four sessions feature complimentary backing from Henry Brown and trombonist Ike Rodgers. Rodgers played rough “gutbucket” trombone, using a variety of tin cans, liquor glasses and other mutes of his own devising. Before moving to Decca in 1934 Moore cut ten songs at two sessions for Paramount in August, 1929 and possibly November of that year. “Black And Evil Blues” was a hit from this session, a dark song underscored by Rodgers’ mournful trombone that would set the tone for many subsequent songs. The song was covered by Lil Johnson in 1936 and Leroy Ervin in 1937. Paul Oliver had this to say about the number: “At times the characteristics of African racial features and color have an ominous significance in the blues, which may hint that they are indirectly related to social problems. So the state of being ‘blue’ is associated with alienation, and is linked with an ‘evil mind’ or an inclination to violence. Both are coupled with the inescapable condition of being black. …That her hearers identified with her theme was evident in the popularity of the blues, which she made four times in different versions.”

© Just A Good Girl Treated Wrong: The Blues Of Alice Moore Part 1

for further reading ▼

Just A Good Girl Treated Wrong: The Blues Of Alice Moore Part 2

Artist descriptions on Last.fm are editable by everyone. Feel free to contribute!

All user-contributed text on this page is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply.