传记

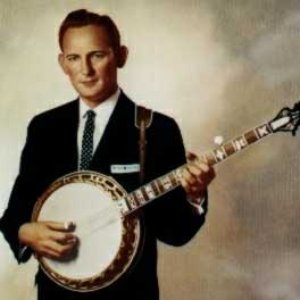

The first time I saw Don Stover play was on a cold and snowy night in central New Jersey in February 1977. A friend of mine had come down to visit from Brooklyn, and we drove from the Rutgers University campus in New Brunswick to Geoff Berne's Englishtown Music Hall in an old beat-up car that either had a broken out windshield, or windows that couldn't be rolled up, I don't recall which. Nevertheless, we were frozen by the time we reached the music hall, and the bad weather was enough to keep all but a handful of people from showing up for a night of music. We warmed up in short order, after enjoying a country dinner of chicken, baked beans, and corn-on-the-cob, but what does seem to have been frozen in my mind was the drive and energy and humor in the shows presented that night by Don Stover and the White Oak Mountain Boys. The level of musicanship I heard made a great impression on me, and, in fact, motivated me to go out and buy my first banjo the following week, but I also learned the difference between a bluegrass musician and an entertainer that night, too. I must have known enough about bluegrass decorum at the time to cringe in embarassment as my friend shouted for the Orange Blossom Special, but Don looked down from the stage into our front row seats and dedicated the "OBS" to him, just as if it was the first time he had played the song. As trivial as it seems, this was my first realization that the fulfillment of a request, or the telling of a story, meant more to most audiences than the speed or execution of a hot banjo lick, and it made quite an impression on me.

It wasn't until ten years later that I finally met Don. I had listened to his music more and more over the years, and while I was gaining a greater appreciation for his musical talents all the time, I also became increasingly frustrated at the lack of new material being released. This feeling was even more pronounced after I heard a terrific live tape of Don playing at the Augusta Heritage Arts Workshop (Elkins, WV) in 1985, certainly putting to rest my assumption that he must not be playing any more. After much soul-searching and account-balancing, I wrote to Don and suggested that perhaps we could make a "living room" tape with some new material for him to sell. To my surprise, he called me back shortly thereafter, and, to make a long story short, we eventually recorded a studio album ("My Blue Ridge Memories") on the White Oak label, which we named after his home town of White Oak (Ameagle), WV. The business aspect of the recording industry has been an eye-opening experience, but throughout it all, it has been a real honor to be associated with someone with Don's good nature, talent, integrity, and optimism. In 1990, Don underwent fourteen hours of brain surgery, was out of intensive care on September 17th, and was back playing on stage at Harper's Ferry on September 19th, which is a good indication of how important playing bluegrass music is to him. Detailed accounts of Don's long career have been reported elsewhere, especially in Bluegrass Unlimited (vol. 7, pp. 7-9; '73) and in Banjo Newsletter (vol. 7, pp. 5-7; '80) and I will leave it to those who are interested to track down the history of Don's tenure with the Lilly Brothers in Boston and other musical ventures. In this interview, I tried to restrict the questions to those I felt had not been addressed previously. We talked between shows of the First Generation (Bill Clifton-Don Stover-Jimmy Gaudreau) at the West Virginia State Craft Fair in Harper's Ferry on June 11, 1995.

BNL: You originally learned to play clawhammer banjo from your Mom and Dad. Can you remember some of the tunes that they played?

DS: "Muskrat goin' through the sand, draggin' his long tail, Sally Ann." And oh, "Cripple Creek," Rovin' Gambler." My Daddy used to sing and play that all the time, and make us kids dance while he did it. "Salt River" was one. I introduced that one to Billy Keith, and he introduced it to Bill Monroe, and they recorded and called it Salt Creek. But we always called it Salt River, and there was some words also to the song. My mother used to sing, "Who's been here since I been gone, pretty little girl with a red dress on."

BNL: "Marching Through Georgia" is an old civil war song. Did you hear that when you were a kid, too, or did you adapt that later?

DS: I heard that when I was a kid. I never heard that on a record, but I heard other banjo old-time clawhammer players around home, they were doing that song.

BNL: Your style has been described as having a driving sound. What do you think that means?

DS: I always played with a pretty strong finger, you know. I never played so soft you can't hear it. If you can't hear it, you ain't gettin' nowhere, you know? So I always laid some heavy arm on it when I pick it, and clawhammer, either one. I found out if I play too soft, I lose – I call it accuracy. I lose a lot of notes in between if I lighten up too much. I got to really feel those strings.

BNL: What qualities do you think make a banjo player interesting to listen to?

DS: Tone. Notes don't worry me too much, I don't use too many of those, no how. I don't criticize nobody, but if you use too many notes in a good song, you've got a banjo solo there or something. I always like to play light behind somebody that's singin' and do a little fill in here and there to make him sound good.

BNL: How much tone is dependent on the musician, and how much is dependent on the instrument?

DS: If you've got a good instrument, then you're really in control. You're the boss, and you feel it inside. You go on a stage to a show, and your banjo's broke down and you've had to borrow one or something, and it really doesn't have much quality to it – your soul's not in that. You lose a lot of stuff on your show because your banjo isn't right.

BNL: In the past, you've mentioned, in addition to Earl Scruggs, Rudy Lyle and Don Reno as major influences on you. What made those guys special to you?

DS: Well, I mention them because there weren't many other banjos playing in that day. Earl's the only banjo player that I ever heard. I talked to Howdy Forrester, Roy Acuff's fiddle player, he told me the same thing. He said, "Earl Scruggs was the first man I ever seen play a banjo like that." So I heard Don Reno, who came in with Bill Monroe after Earl's contract run out, and Don worked at doing Bill's stuff like Earl played it. I don't know, it was a disappointment for both me and my brother to see Earl leave Bill, 'cause we listened to them every Saturday night on the battery radio. But Rudy didn't come along until after Don Reno. I had been playing Earl Scruggs' up one side of the wall and down the other, even before Reno come along. I'm not braggin.' DonÕs eleven months older than I am, so he could have been playing a little bit before me, I don't know. We didn't get together and figure it all out – check the months and the weeks and the dates and the years. But I like Don's pickin,' I really do. But then he improved – his banjo pickin' improved from '49, '50 right on through, and kept improving right to his last day.

BNL: He really carved out his own style.

DS: You can believe me, that's awfully hard to do today, too. 'Cause how many banjo players are there in the United States today? 547,000? I just like to go on a stage and play my banjo the way the song's supposed to be and all that. Do my thing. People declare today that I have a style, and I don't know how they distinguish it. I would guess every man has his own style of playing the banjo.

BNL: The banjo you had in the late '60's and early '70's had no inlays in the fingerboard. Why was that?

DS: I wore one neck out; just wore the frets plumb off of it, working with the Lilly Brothers seven nights a week. I got a guy to chop me out one within a couple of days, and all he got to do was fret it, and I had to have it, and I took it without the pearl. So I played without any markers on it whatsoever. It didn't bother me. Gosh, we played so much in Massachusetts, I believe that I could have closed my eyes and put cotton in my ears and have played just the same. The more you play, the better you get at it, I don't care who or what it is.

Hank Edenborn adds: I have put together a detailed discography of Don Stover's recording career to date, which includes each recorded song and its approximate key, recording personnel, a bibliography of articles about Don Stover, rare photos of Don and material related to his career, and a listing of banjo tabs in print. If you are interested in obtaining a copy of this discography, it is available for $6 ppd at the address below.

With any luck, more Don Stover recordings will be released soon. A live recording of the Lilly Brothers and Don Stover made at the Hillbilly Ranch in 1967 is being prepared for release by Hay Holler Records, and live shows of Don playing with bluegrass veteran Mac Martin in 1991 are in preparation at White Oak Records. Another studio recording session by Don for White Oak is anticipated in 1996. – Hank Edenborn

每个人都可以编辑 Last.fm 上的艺术家描述,欢迎奉献您的力量!

此页面所有用户贡献的文字均根据 Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 授权;可能适用其他条款。